Education/

Curriculum

The Stone Tells Our Story

What is the Hardaway Site and why is it important?

The Hardaway Site is the oldest archaeological site found, so far, in North Carolina. Archaeologists date the site back to 12,000 years BCE. That was a very long time ago and humans, as well as the Earth itself, have undergone many changes since then. While being the oldest site in North Carolina is important, Hardaway’s most valuable contribution to archaeology (the study of human history through the excavation and analysis of artifacts and other physical remains), is that an archaeologist named Joffre Coe was able to use the projectile points found here to develop an arrangement of projectile points and artifacts associated with certain time-periods that other archaeologists could follow. This was a huge development that helped archaeologists in the Eastern United States to accurately date and describe other archaeological sites.

Where is the Hardaway Site?

Mammoth

The Hardaway Site is located along the Yadkin River near the present-day town of Badin, Stanly County, about 40 miles northeast of Charlotte, in the piedmont of North Carolina. It is located about 5 miles north of Morrow Mountain State Park which contains some of the best outcrops (an outcrop is the part of a rock formation seen above ground) of a stone called rhyolite in the United States.

The Perfect Spot

What was the environment of the Hardaway Site and the piedmont like 12,000 years ago?

At the earliest dates of the Hardaway Site, there were probably megafauna (which comes from Greek “large” + Latin “animal), which may have included mammoth, the giant ground sloth, the saber tooth tiger, and flora (Latin “plant”) associated with the Ice Age alongside what would be considered contemporary plants and animals. The Uwharries were covered with boreal forest of pines, spruce, and fir trees. During this time, there were still massive amounts of water held in glaciers and ice sheets that came as far south as what is now Ohio, meaning that the Atlantic Ocean’s coastline was several miles further out than it is today.

This resulted in slightly different river courses than what we know today. In the Paleoindian period, rivers flowed much faster, and may have been deeper. As the climate warmed from the end of the last Ice Age (which scientists call the Pleistocene epoch) 11,550 years ago to the beginning of the Holocene (our present epoch), the natural environment began to more closely resemble the environment of today.

Why was the river important?

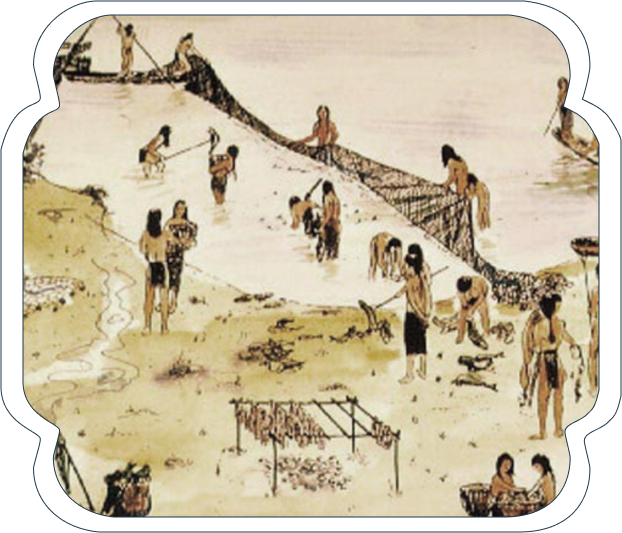

Hardaway is located at the Narrows of the Yadkin River. The “Narrows” refers to a natural constriction (or narrowing) of the Yadkin River. The Narrows have long been associated with seasonal runs of shad fish in the spring, which is a possible explanation for why people traveled from the Morrow Mountain quarry to camp. Shad runs occurred like those of salmon in rivers in the Pacific Northwest. In the recent past, prior to the construction of a dam in the Narrows area, shad swam upriver to spawn. Unlike salmon, most shad return to the sea after the breeding season. This multitude of fish congregating in the Narrows each year made them very easy to catch for food until the rivers were dammed up to make electric power in the early 1900s. Traditionally, fish were caught in nets suspended from poles driven into the riverbed close to shore. Although there are no shad runs in the Yadkin River today, there are ethnographic accounts of shad and remains of fish weirs in the river.

What was life like for the ancient Native Americans?

Beginning around 12,000 BCE people entered the Hardaway Site and camped there. This site was used as a base camp intermittently over thousands of years. Artifacts found at Hardaway span all the cultural periods of prehistory in North America. These periods are the Paleoindian period (12,000 BCE-8,000 BCE) the Archaic Period (8,000 BCE- 1,000 BCE) the Woodland Period (1,000 BCE -1600 CE) and the Mississippian Period (1,000 CE-1700 CE).

Up until the late Archaic Period, the Native Americans using the Hardaway Site were hunter-gatherers and lived in small bands of 25-100 individuals. They probably joined other small bands periodically for ceremonies, feasting, and other social interactions. The actual number of people in a band varied and could be related to resource availability. In lean times, when food was scarce, people lived in smaller, extended family groups. In times of greater resource abundance, bands could join together at places like the Hardaway Site.

Families netting and smoking Shad

The ancient Native Americans were highly mobile, and they did not have permanent homes. Sometimes we think of hunter-gatherers as less advanced than us, but they had a vast knowledge of their environment and the resources of the piedmont. They knew precisely where their next meal was coming from. Farming, or agriculture, is a relatively recent innovation for Native Americans and was not part of the lifeways of their ancient ancestors. Intensive agriculture was not developed in the southeastern United States until around 1,000 CE.

American Indians ate, slept, and camped at the Hardaway Site for a few days or even weeks to collect raw materials and prepare stone tools. They would then continue their seasonal travels around the area we know as the piedmont of NC. The amount of time hunter-gatherers spent at Hardaway was probably related to the availability of food resources in the general area.

These hunter-gatherers lived on the land where we live today. They are the founding population for all later American Indian groups in the state, although it is very difficult to trace lineages to specific groups or tribes.

How do we know people moved around the piedmont?

The evidence for moving around the region can be found in the wide distribution of rhyolite flakes and artifacts that were discarded in a 200-mile radius around Morrow Mountain. They quarried stone in the Uwharries, carried it with them across the piedmont, and discarded it after use. Many of the projectile points found today in North Carolina are made from Morrow Mountain rhyolite.

Why don’t we know more about the lives of these earliest peoples?

Since the Hardaway Site existed so long ago, there are many things we simply do not know. If items are not preserved in the ground for the archaeological record, archaeologists must make inferences, or educated assumptions. Most natural items that the Native Americans used like animal hides, wooden spear shafts, and grass rope fish nets, simply do not preserve for 12,000 years. That does not even include the languages, skin colors, social structures, ceremonial and spiritual traditions of these people living over this vast amount of time. Moreover, no written records exist because these people relied on oral traditions to pass down stories and life lessons.

Archaeologists sometimes make inferences about groups of people and how they lived by using ethnographies, or studies of the social interaction of more recent hunter-gatherer groups. However, this presents some challenges, as there are no ethnographies of hunter-gatherers from similar environments to North Carolina. Most are from southern Africa or Australia. One such inference archaeologists have made about the American Indians at Hardaway, is that shelters were simple constructions of grasses and animal hides draped across thin trees.

What do projectile points tell us about the age of the Hardaway Site?

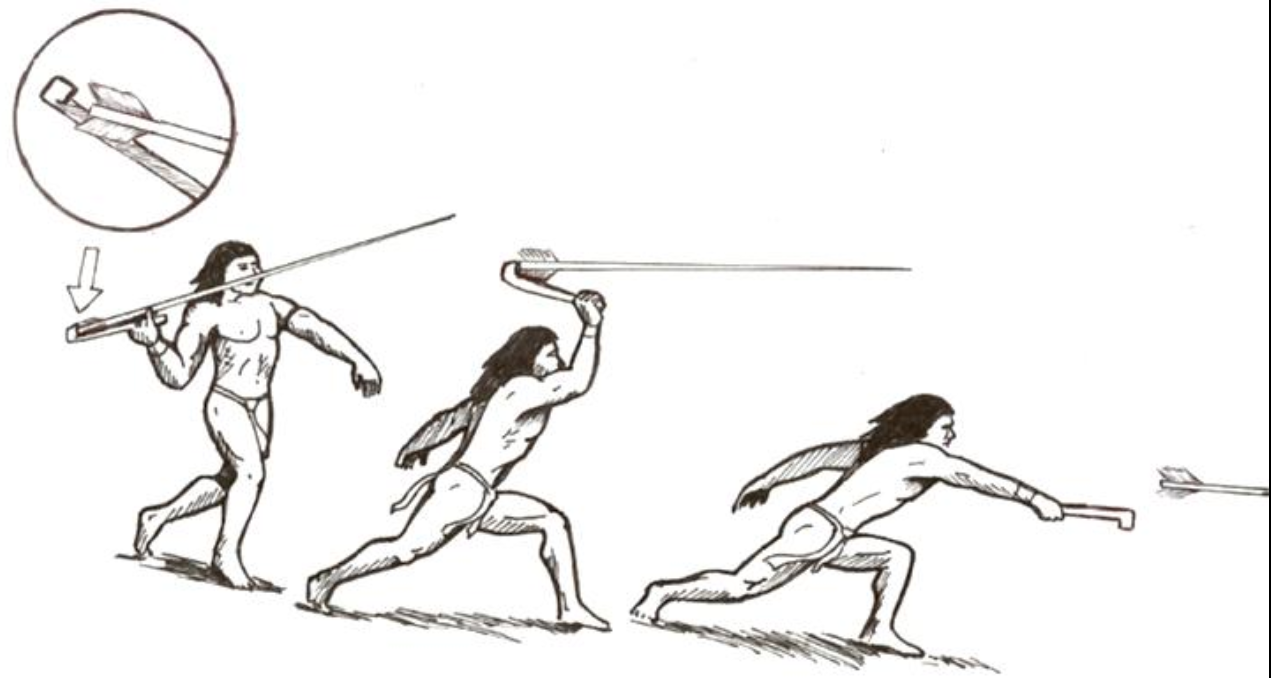

Atlatl - Spearthrower

In the 1950s, archaeologist Joffre Coe compiled data from the Hardaway Site, along with other sites from the region (Doerschuk, Lowder’s Ferry, and Gaston), to create a projectile point classification system for the North Carolina piedmont from the earliest inhabitants to possibly the European contact period. He was able to connect the four sites because they shared artifact styles. Coe established an arrangement of projectile points and artifacts associated with certain time-periods that other archaeologists could follow. When carbon-14 dating was invented, archaeologists were able to tell the approximate age of a site or dirt layer of a site based on organic material found next to the artifacts.

The emergence of carbon-14 dating was a huge innovation from chemists that greatly benefited the field of archaeology. This allowed archaeologists to know the actual ages of artifacts, or at least the organic materials (wood, bone, seeds, etc.) that were found with them in the ground. Previously, archaeologists could only speculate on the age of artifacts.

What is Rhyolite?

People made stone tools from the rhyolite, including:

- Projectile Points (spearheads) – commonly confused with arrowheads, although no Native American arrowheads existed until around 500 AD. The projectile points were attached to the end of a long wooden pole (spear) to throw at animals to kill for food and clothing.

- Quarry blades – also called quarry blanks, a stone that was broken at another location to be used to make a tool later. Similar to a preform which is explained below.

- Scrapers – most likely used to scrape the hide off of an animal.

- Drills – used to drill holes through animal skin, other rock, shells, and wood.

- Atlatl weights – weights used to balance the end of the atlatl not attached to the spear.

- Engraved slate and river stones – these are decorated stones, the primary function is unknown, possibly to sharpen points of bone or other stone tools, or simply for art; these were mostly made of sandstone.

Stone tool styles changed over time as people developed new technologies and became better adapted to their environments. Tools have changed to help people better utilize the natural resources around them. Many tools were created to serve more than one function and the people creating the tools did this to ensure the efficiency of what they had to carry. The hunter-gatherer tool-kit had to be portable, so the people would have done whatever possible to cut down on the amount of items/weight to carry. This is signified by the almost constant reworking of tools, and tools with multiple functions.

What are preforms and how were they used?

Preforms were stone implements that had been shaped from a quarry blank but had not been worked down to a specific tool yet. Preforms could be used as they were, or worked further into a specialized tool for a specific purpose. They were much lighter than a big chunk of rock for a mobile group of people to carry around with them. Stone tools also often break, and it was important for these people to be able to have preforms to replace broken tools when they were far away from a source of stone.

What story does the stone tell?

Many rhyolite flakes were found at the Hardaway Site, Morrow Mountain, and nearby. However, there were no sources of rhyolite at the Hardaway Site. Archaeologist Randy Daniel was unsure about where the rock found at Hardaway came from. During several visits to Morrow Mountain, large areas of rhyolite flakes were found covering the sides of Morrow Mountain. There are about 1.5 million artifacts and over 15 tons of artifacts and stone flakes stored at UNC-CH that were collected from the Hardaway Site. These 15 tons (or 30,000 pounds) of stone in the collection weigh about the same as two school buses full of children and most of the Hardaway Site has never been excavated.

Randy Daniel worked with geologist Robert Butler who confirmed the flakes at Morrow Mountain had the same mineralogical composition as those of the artifacts found at Hardaway. From this, they determined that the Native Americans quarried the rhyolite at Morrow Mountain, and then brought the stone to Hardaway where they camped while making their tools.

What is archaeology?

A subfield of anthropology, archaeology is a social science. Archaeologists approach their theories in the same way that other scientists do. They construct hypotheses, develop a range of possibilities and then see if they can disprove any of these possibilities.

Field Survey (Finding a Site)

Before an archaeologist can excavate a site, he or she must find one. Archaeologists sometimes use maps and documents to find places that people wrote about or knew of long ago. Some sites are too old to be on any map or in any documents. Traditionally, field surveying was done by walking across a recently plowed field to try and find artifacts brought up to the surface by the plow. Areas with a lot of artifacts on the surface can signify a site below. Modern field surveying includes aerial and satellite photography (GIS). Often the outline of structures in the ground can be seen from an overhead shot. Objects in the dirt can also affect the color and growth of vegetation on the surface.

Many more sites are found than are excavated. It’s estimated only 1% of known sites have been. Field surveying can be very helpful in understanding population spread and settlement patterns of ancient peoples. Archaeologists use field surveys to map the sites of a geographic area.

Excavation

Typically, the oldest artifacts are found at the lower layers of an excavated site. Archaeologists take care to record the context of artifacts discovered through excavation. Archaeologists often use grids to aid organization and to create smaller areas to work in. These squares may be related to structures believed to be beneath the surface, or may be simply gridded in regular intervals.

Soil is deposited in layers of similar material over time. Today, archaeologists excavate sites layer by layer to maintain the context of artifacts. This way they know all artifacts found in one layer are from the same relative time. Archaeologists use trowels, brushes, and sifters to ensure that they discover as many artifacts as possible without harming the artifacts.

Maps are made of archaeological sites at several points during the excavation process. These maps include detailed drawings of site features and some artifacts, as well as elevation and any other helpful information. Archaeologists complete lots of paperwork during excavation to accurately record the process of the excavation, describe the artifacts, and features of the site, and record the collection of artifacts from the site. Documentation ensures that archaeologists can always know the context of the artifact.

Analysis (Archaeology Lab)

Archaeologists confer with scientists in other disciplines to make sense of their evidence and to complete the story told by the artifacts. Generally, all the artifacts found during excavation are taken to the archaeology lab to be cleaned and analyzed. Analysis of artifacts includes classifying them into like groups, chemical analysis to discover molecular make-up of the material, use-wear studies to determine how artifacts were used, and experiments with reproductions to better understand how artifacts were made or used. Many experiments are expensive and can sometimes result in the destruction of an artifact, so archaeologists have to be selective about what techniques to use.

Publication (sharing knowledge)

In order to inform fellow archaeologists and the general public about the work they have done, archaeologists publish their findings and conclusions. Publications generally include a description of the excavations, descriptions of artifact analysis, collaboration with other archaeologists and scientists, and conclusions that take each of these into account. Archaeologists no longer publish the exact location of sites to protect them from looting. Archaeological publications are essential in educating others about the past and can aid in finding funding and promoting interest in archaeology.

Resources and References

- Coe, Joffre L. 1964 The Formative Culture of the Carolina Piedmont. Transactions 54 (5) Philadelphia: American Philosophical Society.

- Daniel, I. Randolph. 1998. Hardaway Revisited: Early Archaic Settlement in the Southeast. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

- Davis, M. Elaine. 2005. How Students Understand the Past: From Theory to Practice. Walnut Creek: Altamira Press.

- Price, Margo L., Patricia M. Stamford, and Vincas P. Steponaitis, eds. Intrigue of the Past: North Carolina’s First Peoples. Chapel Hill: Research Laboratories of Archaeology, University of North Carolina.

- Ward, Trawick, and R.P. Stephen Davis, Jr. 1999. Time Before History: The Archaeology of North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.