Hardaway’s

Historic Journey

Morrow Mountain's Unique Rhyolite And the Hardaway Site

Overview

To speak of hunters and gatherers is a description of a group of people during a very small segment of their lives. It is like calling us factory workers, office workers or shoppers. Hunter-Gatherers were just as complex as us. They had societies that were very involved. They had interactions with many groups of people.

They had rituals and rich symbolic lives. They did many other things than hunt and gather. The society lived this lifestyle of hunting and gathering for thousands and thousands of years, and we should say over millions of years. So, hunting and gathering is the normal way of acquiring food. Far more normal than what we do today. In a way they are the norm, we are the abnormality. It is a lifestyle, one on the verge of extinction though it lasted for millions of years. We should look at it as a very successful adaptation.

-Silvia Tomaskova, formerly a Prof. of Anthropology at UNC

The First Carolinians - the First Peoples of southeastern North America - and central Piedmont traveled down the Yadkin-Pee Dee River Basin over 13,000 years ago. They likely traveled to eastern North America on a long multigenerational journey that started in North Asia. They crossed the Bering Strait land bridge, formed from massive amounts of water frozen in huge glaciers during the last Ice Age, and entered northwestern North America. These Paleoindians were experts in their Stone Age world’s social and cultural practices and began to spread in large numbers across North America. One of their essential skills was locating the ideal stone for making tools and spearpoints. The Uwharrie Mountain range comprises ancient volcanic cores that are sources of metavolcanic rhyolite. Atop Morrow Mountain, Paleoindians located outcrops of a metavolcanic, cryptocrystalline, high silicon, high quartz, rhyolite (a similar composition to obsidian) that could be used to craft exceptional spearpoints. The unique geography of the Uwharries also contributed to other natural occurrences, such as seasonal shad runs up to The Narrows of the Yadkin, a natural canyon formed by the Yadkin River that flowed through a break of a high ridgeline. The west side of this ridge provided long river views and easy access to spawning shad. Located within five miles of the rhyolite source on Morrow Mountain, it was an ideal campsite. This gathering place would be used often for around 13,000 years. For over seventy years it has been called the Hardaway Site, after the Hardaway Construction Company, whose workers camped there while building the Narrows Dam in 1917.

During the Pleistocene period, massive glaciers covered around one-third of the Earth’s landmass, and ice sheets in North America extended as far south as Ohio. Sea levels were almost four hundred feet lower than today, creating land bridges like Beringia at the Bering Strait, connecting Asia and North America. This land bridge allowed the migration of animals and people into North America, though recent anthropological studies have suggested that humans entered North America in multiple ways.

These glaciers began melting and retreating around 15,000 years ago when mastodons, mammoths, and giant sloths still roamed the boreal forests of the Uwharries and Piedmont. Conifer (cone bearing) trees characterize boreal forests. These megafaunas were destructive of the boreal forest, tearing up plants and knocking trees down, aiding the creation of savannas and grassland for grazing. Much later, American Indians began to help maintain these productive grasslands with controlled wildfires. As the climate warmed between the end of the Pleistocene epoch and into the Holocene epoch, bison, horses, elk, and deer became prominent game animals, and deciduous forests of oak, walnut, hickory, and maples began to thrive. Abundant anadromous fish (shad, herring, and sturgeon that migrate up rivers from the Atlantic Ocean to spawn) laid their eggs in the turbulent waters rushing through the Narrows of the Yadkin just upstream from the confluence of the Yadkin and the Uwharrie rivers.

Historic Culture

"Of the many surprises discovered during the early days of archaeological research at Hardaway, the biggest was the sheer number of artifacts found. While digging 5’x5’ excavation pits, it was not uncommon to see hundreds of stone artifacts in just several shovels full of soil. Likewise, the sides of Morrow Mountain contain many thousands of tons of knapped stone debris." Dr. Randolph Daniel, Former Chair of Anthropology at East Carolina University, received his Doctorate from UNC-CH and is a Hardaway Site expert.

"If you were an American Indian living in what is now North Carolina you would know about the unique rhyolite at Morrow Mountain and about the Hardaway Site,” Daniel said. It was a known source of high-quality stone for making exceptional spearpoints, and it was an excellent place in the spring for netting shad. The ample deer, bison, elk, bears, horses, pigeons, and beavers of the Uwharrie were also food sources. Rather than migrating after herds, American Indians could have stayed longer to take advantage of abundant resources. The Narrows of the Yadkin and bald Morrow Mountain were easy to find along the Yadkin-Pee Dee River Basin. Hardaway became a central gathering spot for American Indians for thousands of years. This site connects Paleo, Archaic, Woodland, and even Mississippian cultures to the more modern tribes that were created through the 16th, 17th, and 18th centuries. Hardaway is not only about the events, practices, and cultures of the ancient past but also a bridge to the past for American Indians today. By studying the Hardaway Site, the depths of ingenuity and agency of American Indians in North Carolina, South Carolina, and the Southeastern United States become known.

Morrow

Mountain’s

Stone Quarry

American Indians had a very advanced Stone Age Culture, highly adapted to the natural world in the Southeastern United States.

They were highly skilled at hunting and gathering fish, plants, and berries. As a group, they could surprise and kill mastodons, mammoths, and giant sloths that provided days of food for their small communities of 25-100 people, showing high degrees of communication and coordination. Such groups migrated after food sources routinely and would sample stone from different regions.

The stone in the Uwharrie Mountains was superior to other areas because the Uwharries were a volcanic island chain, with geological processes that created a stone we know as rhyolite. The purest, fine-grained, cryptocrystalline, igneous rhyolite was located by American Indians around the top and sides of Morrow Mountain. They used their keen knapping skills to turn these stones into exceptionally sharp, durable, piercing spearpoints. For over 13,000 years of occupation at the Hardaway Site, American Indians from what is now North Carolina, South Carolina, and parts of Virginia traveled regularly to utilize the unique rhyolite covering the top of Morrow Mountain.

Today, on the Mountain Loop Trail around the top of Morrow Mountain, one can see the product of thousands of years of worked stone debris and tons of that debris left by American Indians on the mountain. Much of that initially worked stone was taken by American Indians back to the Hardaway Site, about five miles away, for additional knapping and sharpening. Spearpoints made of Morrow Mountain rhyolite have been found in significant numbers across North Carolina, South Carolina, and Virginia. Trade networks among the Native Americans spread points and tools made of Morrow Mountain rhyolite across the eastern seaboard.

Shad at the Narrows

of the Yadkin

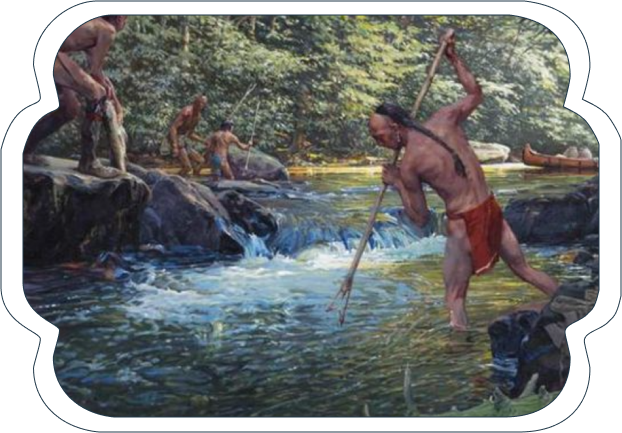

There are many reports and stories of the seemingly limitless shad that swam up the Pee Dee River from the Atlantic Ocean to spawn (lay and fertilize their eggs) in the spring. The swift, often turbulent waters at the Narrows of the Yadkin were an ideal place for the fish eggs to begin their journey to the Atlantic Ocean. Although shad would be reported along the Yadkin as far north as Salisbury and even Wilkesboro, the Narrows was the fall line of the Yadkin River and the best place to capture the most sizable number. Shad and other fish migrations have been noted by anthropologists as a major factor in increasing regional populations of American Indians and those cultures becoming more sedentary, staying in one place for more extended periods.

The most significant concentrations of settlement sites would be found at geographic locations that promoted fish spawning, like the Narrows of the Yadkin. The fact that the Hardaway Site, the Doerschuk Site, and the Lowder’s Ferry Site are close to the Narrows help illustrate its importance.

An early geological survey described the Narrows: “At the upper end, before reaching the Narrows, the river is nearly or quite 1,000 river feet wide, from which it suddenly contracts, entering a narrow ravine between the hills, which rise abruptly on either side with rocky and almost perpendicular banks, and through which it pours with great violence, preserving for a distance of about a mile an average width of not over 150 feet, while in some places the width is only 60 feet. No description can do justice to this place, which is one of the most wonderful spots that can be found in the south…” Bulletin North Carolina Geological Survey No.8 1899.

Colonial America greatly depended on the American Shad, called the Founding Fish by author John McPhee, along almost every major coastal river in the Eastern United States. They swam up the Great Pee Dee River from Georgetown, South Carolina, in overwhelming quantities to spawn in the 17th and 18th centuries. In the 19th Century, from Georgetown up to the Narrows of the Yadkin shad were still regularly harvested. Dams in the early 20th century began to gradually block sections of the river, making it almost impossible for shad to migrate, thus cutting much of North Carolina off from this bountiful food source.

According to archaeological evidence, long before European contact, American Indians with fishnets, and fish weirs skillfully harvested vast shad at the Narrows of the Yadkin and along sections of the free-flowing Pee Dee River.

Through sun drying and smoking techniques, a dependable and long-lasting food resource was utilized by the American Indians who regularly gathered at the Hardaway Site above the Narrows to make their points and tools.